Author: Sid Ruttala

Some Context: Why Nuclear?

The immediate thing that comes to mind when one mentions “nuclear energy” isn’t necessarily one that makes it amenable to be bullish on the sector. Images of Chernobyl and Fukushima come to mind immediately or at best The Simpsons shenanigans regarding it, with Homer making a cake of himself at the Springfield Nuclear Power Plant or countless meltdowns and accidents over the show’s thirty year tenure (think about that, one of the most popular and widely circulated pieces of media of the last three decades consistently associates nuclear with bad things/accidents, all lorded over by an evil billionaire in Mr Burns). But the reality, in this author’s opinion (not necessarily TAMIM’s), is rather different. Nuclear energy has provided, and continues to provide, the world with stupendous amounts of clean, emission-free electric power. After all, how many people are aware that coal has killed far more people than uranium?

Perhaps most importantly, nuclear energy is a zero-emission alternative. For those of you who don’t understand the actual process, it uses fission (i.e. the splitting of atoms) to produce energy. The heat created through the fission process is turned into steam that then goes on to turn turbines. If we take the Nuclear Energy Institutes (NEI) data at face value, in 2019 the US’ use of nuclear power generation avoided the emission of more than 476m metric tons of CO2 into the atmosphere. Let me put this in context, it is the same amount released by around 100m cars and more than the combined output of all other green energy put together.

As emerging markets such as India, and others across Asia, continue to grow their economies and thus their energy consumption, it will become imperative for them to build upon their nascent power generation sectors. This is especially so as energy deficient nations such as India need to sustain their middle class and increasingly urbanized population. For example, 60% of the Indian population still lives in rural areas and will continue to shift to urban areas as the economy transforms from its agrarian roots, putting upward pressure on energy demand.

The only currently viable economic alternative for nations like India and China is coal. Given the aversion to fossil fuels and increasing pressure to reduce emissions, there will be a marked incentive for such nations to develop their nuclear footprint. This is because in densely populated nations, the most important factor when it comes to energy production is not only cost but also land footprint. It is not only expensive but downright irrational to build wind-farms where land scarcity is a significant issue. A typical 1000 megawatt nuclear facility for example requires less than 2.5 square kilometres whereas you would require 360x that in order to get the same magnitude of power generation from wind farms or 75x that space for solar photovoltaic plants. While this might change with advances in battery technology (harvesting power in land-rich nations such as Australia and exporting capacity) and increased efficiency across renewables, the scale and magnitude of the increased energy demand does not make this a viable alternative. For example, recent research from BP forecast India’s energy demand alone to grow by 156% by 2040 and if current trends are any indication, then over 58% of this will be met by coal with a subsequent increase 116% in CO2 emissions. In order to find credible alternatives we are likely to see Indian governments looking to nuclear for energy production, something that Australia was grappling with during the final years of the Howard government where the potential for uranium exports to India was effectively shelved by the election of the Rudd government.

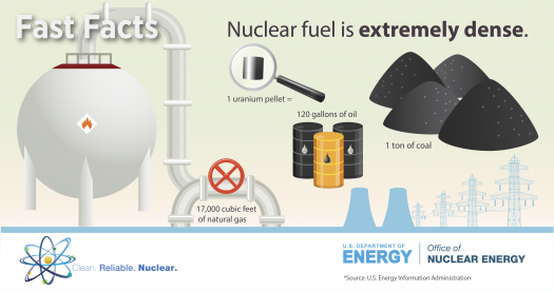

A common argument against also stems from the waste produced but this is also completely misunderstood. One gram of uranium produces about as much energy as a ton of coal or oil and correspondingly, the actual waste is about a million times smaller, and only about 3% of the fission products are vitrified, the rest reused and recycled. For example, all of the waste produced by the US nuclear energy industry could in fact fit onto a football stadium at a depth of less than 10 meters.

Where Is The Money?

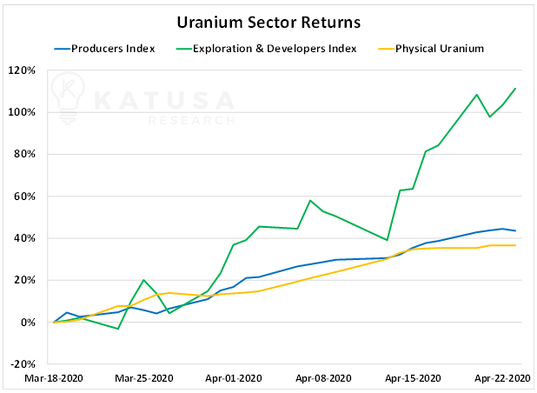

So now that I have got that particular rant off my chest, let’s move onto the actual numbers. The debate around nuclear has seen a resurgence in recent years only as a result of the Tweeter-In-Chief’s investigation into Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act, the short story of which is the reliance of the US upon uranium imports as opposed to domestic production. The very reason that some of the better recent performers in the space have been companies like GTI Resources (GTR.AX) with projects across Utah.

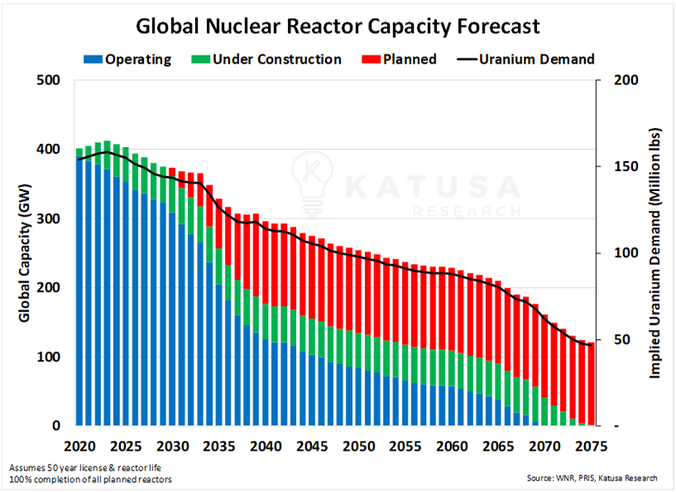

In terms of the actual numbers though, the prospect of nuclear energy is out of fashion at this point with planned increases in reactor capacity declining and many of the existing and operating reactors likely to be decommissioned without replacements over the next fifty years.

Why Can One Be Bullish?

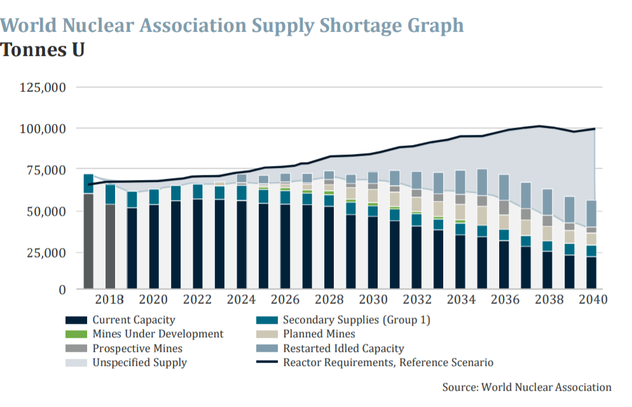

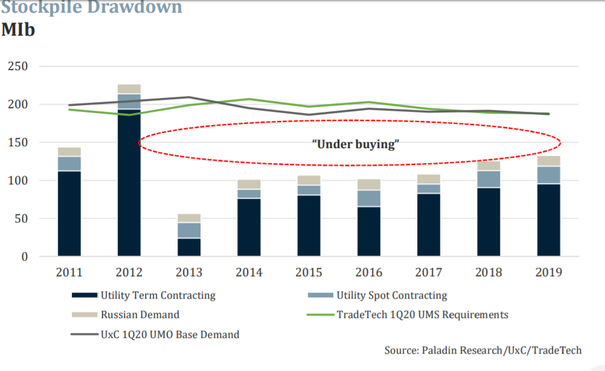

For one thing the supply-side gets rather interesting. Due to massive under-investment into the sector, we have seen consecutive quarters of decline in the actual production of both uranium and plutonium. Most of the global supply is dominated by Kazakhstan at 30% and Canada second. Australia is a very distant third despite this country being endowed with 30% of the proven global reserves (seems like an unexploited opportunity, doesn’t it).

In terms of the companies, the largest producers are dominated by companies in Russia, Kazataprom and the likes of Uranium One with connections to the Kremlin. As we continue to see aggressive stances made between Russia and the US we are likely to see downward pressure upon the actual supply, much the same way as sanctions against Iran and Venezuela suppressed supply in the oil markets. The Khazhak supply is likely to be re-oriented towards China (I would hazard a guess that western economies will turn to Australia’s largely untapped reserves in response). And so, while one need not be overly-bullish in the short-term based on the demand picture, the changing geopolitical picture will (we feel) lead to a gradual disentanglement of the actual prices. On-the ground prices in China, for example, are likely to be less than the global spot price.

This also creates rather good incentives for miners listed on the ASX with US assets and/or Australian exports of the finished product (with, one would hope, export restrictions to India lifted, the logic of exporting to China but not India defies us).

How To Play This?

For the conservative investors, BHP and Rio continue to have significant Uranium assets that look set to benefit from any advances in price and the capacity to increase production should prices move higher. BHP, by the way, produces around 3364 tonnes while Rio produces 1016. For the more adventurous, the old market darling Paladin (PDN.ASX), with 35m USD in cash reserves, requirement for less than 10m USD in spend and the restarting of their Namibian operations, looks attractive. The cost of production for its operations is also around 27 USD/lb and assuming a 45 USD/lb short-run (12-24 month) target we will likely see the share price more than double to 25c. For the exceptionally adventurous, GTI Resources (GTI) has been kicking goals in its exploration projects across Utah and is likely to see support from policy makers to get the projects up and running over the next 24 months.

While it would be fantastic if solar, wind and battery technology advanced enough and became cheap enough to cater to humanity’s energy demands, the reality is they currently don’t. Some additional clarification around this investment thesis too, Uranium as an investment is something I consider to be higher up in terms of the risk profile at this stage. But, should prices come back to economic equilibrium, it should reward the patient investor disproportionately.