Author: Sid Ruttala

Before proceeding further, a disclaimer. We are experts in neither the field of medicine, pharmacology nor epidemiology. As such, what follows is simply an investors quest to understand and find opportunities. Moreover, throughout this piece a great degree of data is ascertained from the International Federation of Pharmaceutical Manufacturers & Associations (IFPMA), given the lack of nuance (in this author’s view) provided vis-a-vis theoretically independent agencies such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and our very own Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). Nevertheless, we shall try and keep the argument as impartial as possible.

Background & Context

For the history buffs among you like myself, this is one sector whose evolution has never ceased to fascinate and tells the story of human ingenuity and enterprise. What began with local apothecaries, expanding their traditional role distributing botanical drugs, turned first into wholesale manufacture, not least aided by discoveries in morphine and quinine, to now becoming a sophisticated global industry central to modern economies (as was illustrated in our most recent global pandemic). My own fascination came about from reading into the prolific use of Laudanum for the most mundane of problems in the Regency Period to the opioid wars that led to the handover of Hong Kong to the British Empire. That particular tangent aside, let’s look at the nature and structure of the modern pharmaceutical industry.

It may come as no surprise that it can be quite difficult to disentangle the structure of the industry and the regulatory framework from its evolution in the USA. From its rudimentary form of oversight starting as a result of early outbreaks of tetanus and distribution of contaminated smallpox vaccines (though even here we have seen instances of regulatory capture arguably as recently as the Nixon administration’s War on Drugs) and passage of acts such as the Biologics Act of 1902; the modern regulatory framework has evolved to create a diverse range of actors both private and public with national bodies, such as the FDA in the US and TGA domestically, becoming the final and peak arbiters. With that, lets look broadly at the process of firstly bringing new drugs/treatments to market.

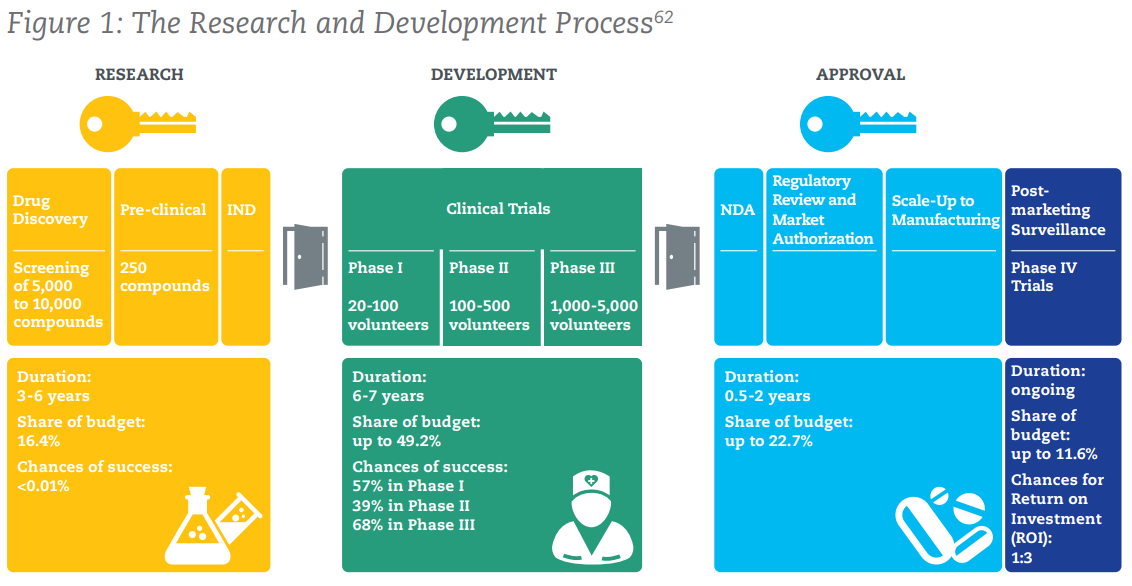

The above figure shows the process by which a new drug/medication is brought to market. To sum up some numbers that may be truly eye-opening, here are some key points:

- 2.5% – 5%: The success rate of compounds passing through the screening process to proceed to pre-clinical trials.

- Chances of Success: <0.01% in pre-clinical, 57% in Phase 1, 39% in Phase II, 68% in Phase III

- 9.5 – 15 years: The average time it takes for a new treatment to go from initial screening to market.

- US $2.6bn: The average cost of bringing a successful medicine to market. Some more context: this was US $179m in the 1970s…

More concerning than the above numbers, is the graph below. It showcases the exponential declines in IRR (Internal Rate of Return) from pharmaceutical innovation over time for a cohort of the twelve largest biopharmaceutical companies by 2009 R&D spending. It shows that returns have declined from about 10% in 2010 to just 1.8% as of 2019. Little wonder then for the rather extraordinary underperformance of the sector for shareholders in recent years.

It is perhaps not that particularly difficult to fathom why. Given the likelihood of success in R&D combined with declining IRR, firms are by extension incentivised to increase profitability of existing products (before patent expiration) as opposed to take on the risk of bringing new products. So, on to the next question, why are IRRs declining?

In a world saturated with conspiracy theories, pharma PR debacles and general pushback against the industry, it may not be a popular opinion but the increased regulatory requirements which, although well intentioned, also had the effect of stifling new innovation and increased consolidation of the space. This is the flipside of regulation, creating high barriers to entry most prominently seen within the financial services sector. Across the planet we have increasingly stringent testing requirements and the cumbersome process of receiving regulatory approvals, national health authorities also require companies to track and report patients’ experiences while reporting requirements also substantially raise investment cost (for the duration of time that the medicine is marketed). To put it simply, we remain of the view that the investment and regulatory landscape has swung too far. But, what’s at stake here?

Quickly, for those that think that Covid-19 was a outlier event in terms of the overall impact upon the global economy. $500bn is the estimated yearly cost of pandemic influenza to global GDP. $3tn is the estimated loss worldwide due to antimicrobial resistance, in the form of superbugs, to the global economy per annum in worst case scenario modelling. By 2030 it is estimated that the cost of tuberculosis every year will be $1tn USD.

Current Landscape

With that context, let us actually get to the current reality of the global biopharmaceutical industry. While overall R&D has seemingly declined (and in our view still remains woefully underwhelming given the centrality of global efforts to the overall economy), the sector still remains an outlier in terms of the amounts spent on R&D, 7.3x greater than aerospace and defence and 1.5x that of software and computer services. Great numbers, aside from the massive cost increases involved in the process over the last four decades.

Conversely however, there have been ways in which the pharma industry has evolved in order to tackle the often prohibitive costs associated. New and novel collaborations through joint ventures, including with non-corporate entities such as academia, and cross sector collaborations are just some of the more recent trends. The most recent and obvious example of this has been the global effort to bring Covid-19 vaccines to market in record time; AstraZeneca’s collaboration with Oxford or the creation of the global COVAX initiative alongside public sector organisations such as the WHO, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), and UNICEF (i.e. for delivery) is a prime illustration of the changes that have taken place.

This unique and complex landscape has also led to certain dislocations. For the truly global investor, we are certain at least some may have taken advantage of the growth in generics in emerging markets such as India. That particular country now accounts for close to 50% of global vaccine manufacturing capacity, 40% of generic medicine demand in the US and 25% of the same in the UK. Combine that with a domestic market that has grown in the high double digits for the last two decades, likely to go 3x over the next two, and equities investors in the overall sector would have seen on average return of close to 15x over the last two decades. The growth in the generics market has been the second trend and the centrality of India is the third that remains crucial to understanding the global market.

No longer is the market characterised by blockbusters being bought to market and the exceptional cashflows generated re-used to generate further blockbusters. We have a truly global supply chain, one which many may have become painfully aware of when India’s own bipolar policy response to Covid put the entire global vaccination program at risk. Increased capex is required while patent expiration for existing medicines combined with competition from generics provides massive headwinds to the market. Combine that with an aging population and future growth coming from emerging markets such as India (which require different pricing), for the non-discerning investor, it is a nightmare to sift through.

On the question of pricing, let’s use a simple and quite recent example: the introduction of the first oral treatment for Covid-19 by Merck (MRK.NYSE) which has ascertained regulatory approval (before you get excited, it is not a cure but simply reduces the chance of hospitalisation by 50% if administered within three days of onset). The actual pricing and distribution of the product is likely to be tiered with developed markets such as the US, which has already agreed to buy US $1bn worth of product, being used to subsidize distribution in poorer or emerging markets. This is done through licensing deals with generics manufacturers, though in the instance of Merck they have decided to distribute it for free. Call me a cynic but we are quite certain that, as they bring to market newer versions and are no longer in the limelight, we will see nice little margins ascertained over the next decade or so (not to mention the PR bump in the short term). The development of the drug itself, to illustrate the other point of collaborations, was done in conjunction with Ridgeback Biotheraputics.

Not to be left behind, Pfizer (PFE.NYSE) has also seemingly come up with its own antiviral pill that is 85% effective (compared to Merck’s 50%) if administered within five days of onset (compared to Merck’s three days). Both work in slightly different ways, with Pfizer being a protease inhibitor (blocks the enzyme and multiplication) while Merck’s is a nucleoside analogue (introduces errors into the genetic code of the virus). Pfizer’s own mRNA vaccine and Covid-19 pill is, by the way, a collaboration with German company BioNTech (BNTX.NASDAQ).

The above example of the Covid-19 anti-viral pill illustrates another example of the modern context. Merck effectively giving away its own IP stands in contrast to Moderna and Pfizer’s ongoing refusal to transfer technology to mRNA vaccine producers in Africa, LATAM and Asia. As mentioned, we have a feeling that Merck’s strategy could be a PR coup which we believe puts them in a better place in those particular growth markets for monetization later. For now however, Pfizer has been the frontrunner in terms of its vaccine efficacy as well as in Covid-related research to date.

With that let us finally get to the first security we like and one which we own in the TAMIM Fund: Global High Conviction portfolio, Pfizer.

Pfizer (PFE.NYSE): Investment Case

Unfortunately for the company, the US Treasury (at the time under the Obama administration) issued new rules to effectively prevent the deal (though it was not pointed out). There was a US $150m breakup fee and somewhat lacklustre performance since.

We bought back into the stock in 2019. Why?

For one we feel the company is often misunderstood. Even before their Covid-19 vaccine, they had a strong pipeline of drugs which fit in perfectly amidst an aging and increasingly obese population. Although mature, Lipitor (cholesterol), Viagra and Celebrex (anti-inflammatory) are three core products. This is combined with prudent acquisitions throughout the 2000s (i.e. effectively ensure stable cash flows for the foreseeable future). With the advent of Covid-19 however, we feel that the company has hit a new period of potential growth. Granted, given the global environment and an increasingly confrontational approach to the sector in the presence of vaccine shortages (yes, this is an issue for a vast majority of the global population despite it not being the case in the West), we will see incremental monetisation going forward. As Covid-19 continues to evolve in the presence of vaccines (superbugs are all but guaranteed) and we see continued rounds of yearly vaccinations globally, this will potentially remain a sticky revenue stream. Believe it or not, the real money is likely not made now when there is a great degree of immediate necessity and potential PR nightmares, we expect increased margins over time as the world learns to live with it.

Arriving at the numbers, revenues for the company grew at a stellar 130%. Even stripping out Comirnaty (their Covid-19 vaccine), the company continued to meet expectations with 7% growth. That second aspect is important given that the flipside of Covid has been a decline in OTC medications and healthcare expenditures. We believe that this is due to Pfizer’s unique product line, aside from lockdowns providing a tailwind for Viagra sales, there has been consistent growth across product lines such as Vyndamax (heart failure – transthyretin-mediated amyloidosis), Ibrance (Breast Cancer) and Eliquis (blood clots), all three of which have grown at high double digit rates. On the negative, cost of sales increased close to 41% (granted, a result of vaccine distribution requirements). What is more concerning however is the 5% increase in Selling, Informational & Administrative Expenses (SI&A), this goes back to our point about the increased expense burden across the sector.

What is more interesting, in our humble opinion, is the all important R&D metric, that is the success rate of the drug pipeline. Across all three phases, Pfizer stands out in having a rate approximately 20-30% higher than industry averages; Phase 3, for example, at 85%. Using simpler metrics, PE at 16.2x (compared with the S&P500 at 29.51x) and a dividend yield of 3.3% (don’t use Australian standards, this is reasonably attractive for US equities) with a payout ratio of 52.45%, we expect this to go sequentially higher over the coming two year period.

Over the coming weeks we will continue to explore the pharmacuetical sector. Given the events of last couple of years, it is easy to have Covid-blinkers on when looking at the space but we will look to explore some of the other dislocations and interesting vaccines/treatments currently in develpoment and the opportunities that these present.