Most investors like to think they’re making decisions based on hard numbers. They pore over charts, debate valuations, and argue about whether the economy is heading for a soft or hard landing. But the truth is, the most important determinant of long-term investment outcomes isn’t always what happens in markets. It’s what happens inside the investor.

The ability to take risk and the willingness to take risk are often lumped together. They shouldn’t be. Understanding the difference between the two, and managing that relationship well, can be the difference between building wealth steadily and watching opportunities slip away in a fog of uncertainty.

Ability vs Willingness to Take Risk

Your ability to take risk is an objective concept. It’s determined by financial capacity, the strength of the balance sheet, liquidity, investment horizon, and stability of capital. A sovereign wealth fund can endure volatility that would sink a family office. A retiree has different parameters from a 30-year-old entrepreneur.

Willingness, on the other hand, is a psychological concept. It’s about how much risk an investor is comfortable with, emotionally and institutionally. It’s about what keeps them up at night.

A mismatch between ability and willingness is one of the most common and under-discussed sources of poor investment performance. A portfolio that could afford to be bold but plays it defensively often sacrifices returns unnecessarily. A portfolio that wants to be bold but lacks the balance sheet to back it up is even worse, that’s how permanent capital is lost.

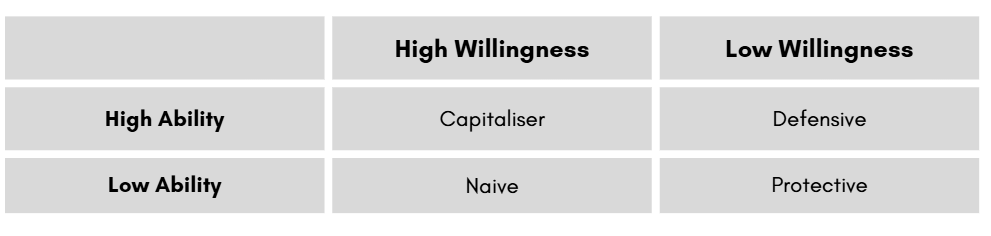

Four Investor Archetypes

A useful way to visualise this is a simple two-by-two framework:

- Capitaliser: These investors have both the means and the stomach to take on risk intelligently. Think well-funded, long-term investors who can handle periods of drawdown without blinking. This is the ideal position to be in, if the risk is taken with discipline.

- Defensive: Financially strong but cautious. These investors accept lower return potential to sleep well at night. In bull markets they may lag, but they tend to preserve capital better in downturns.

- Naive: The most dangerous quadrant. High willingness to take risk with little capacity to absorb losses. This is how speculative manias end badly.

- Protective: Low ability and low willingness. These investors prioritise capital preservation and often underperform, but their conservatism reflects their circumstances.

The point isn’t that one quadrant is “right.” It’s that misalignment is costly. A defensive investor with high ability can afford to take more risk than they do. A naive investor is one shock away from disaster.

Why This Matters More Than Forecasting

Too many investment processes start with macro forecasts: where rates are heading, what earnings will do, which sectors are hot. But none of that matters if the investor can’t stick with the strategy when volatility arrives.

In reality, markets spend a lot of time doing one thing very well, making people uncomfortable. Prices rise too quickly for the cautious and fall too sharply for the bold. Without clarity on risk willingness, discomfort turns into reactive decision-making. Investors sell near the lows, buy near the highs, and call it “bad luck.”

The most successful investors and institutions share one trait: their investment strategy is calibrated to their real tolerance for risk, not the one they wish they had.

The Real Cost of Playing It Too Safe

There’s a certain romance to being cautious. The idea of “protecting capital at all costs” sounds responsible. And for some, it is. But excessive caution for those who can afford more risk can lead to something just as dangerous as loss: opportunity cost.

A portfolio sitting heavily in cash or ultra-defensive assets may protect against short-term volatility, but over the long run it quietly erodes purchasing power and wealth. In an environment of moderate inflation and rising productivity, staying on the sidelines can be an expensive habit.

There’s nothing wrong with being defensive, if that’s where your willingness lies. But it should be a conscious, strategic choice, not the accidental outcome of fear.

Volatility Is Not the Real Risk

Many investors treat volatility as the enemy. Sharp drawdowns feel painful, and traditional finance loves to package risk into neat measures like standard deviation or Sharpe ratios. But volatility is not the same as risk.

The real risk is permanent capital loss, the kind that comes from forced selling, liquidity mismatches, or overleveraged positions that can’t survive a shock. Volatility, on the other hand, is often just noise. A temporary mark-to-market movement means nothing if the underlying business or asset remains sound and the investor has the staying power to ride through the storm.

Ironically, some of the most conservative investors suffer the most from volatility precisely because they treat every fluctuation as a signal to act. Those with longer time horizons, better liquidity, and clear risk willingness can afford to sit still.

Externalities: When Volatility Becomes Dangerous

Volatility becomes dangerous not because of the asset itself, but because of the environment around the investor.

- A fund that prices daily and faces redemptions cannot ride out a storm the way a sovereign wealth fund can.

- A retiree relying on portfolio income to fund living expenses experiences volatility differently than a 25-year-old.

- A board with political or career constraints may feel forced to “do something” when markets turn down.

These externalities mean that two investors can own the exact same asset and experience completely different levels of risk. Recognising this is critical to aligning strategy with reality.

Liquidity, Leverage, and Flexibility

When discussing risk willingness, liquidity and leverage are key levers.

- Liquidity: Some illiquidity can be beneficial, it can anchor investors to a longer-term view. But too much can be dangerous if cash flow needs are underestimated.

- Leverage: Modest, well-structured leverage can enhance returns for strong balance sheets. But it must be paired with realistic assumptions about market shocks and refinancing risk.

Risk willingness isn’t just about attitude. It has to be operationalised into portfolio structure.

Performance Isn’t About Beating Peers

A surprisingly common but flawed goal in investing is “beating peers.” It makes for good marketing but bad strategy. For pension funds, family offices, or long-term investors, the real objective is simple: meet obligations and grow capital prudently.

Beating a benchmark while failing to meet your funding needs is meaningless. Conversely, lagging a peer group but hitting your funding targets is a success. The scoreboard matters less than the scoreboard most people don’t see, the internal one that measures whether your capital is doing its job.

Rethinking Performance Measurement

Short-term performance is often a terrible guide to investment skill. A good year may just mean a market tailwind. A bad year may reflect prudent caution. The only meaningful way to assess a strategy is across a full market cycle, through good times and bad.

A portfolio that keeps up in bull markets but falls less in bear markets compounds more effectively over time than one that chases every rally but crumbles when volatility bites. The willingness to stay the course through a full cycle, rather than demand instant validation, is what separates disciplined investors from tourists.

Practical Investor Reflection: Which Quadrant Are You In?

Before making your next allocation decision, pause and ask yourself three deceptively simple questions:

- What is my financial ability to bear risk?

Consider time horizon, liquidity, obligations, leverage capacity, and funding stability. - What is my true willingness to bear risk?

Think beyond slogans. How much drawdown could you genuinely endure without panic or forced selling? - Are these two aligned?

If not, how should the strategy adjust? More diversification? Different liquidity mix? Less exposure to high beta assets?

This exercise sounds simple. But most investors don’t do it honestly. They anchor to market narratives instead of their own reality. The result is predictable: strategies they can’t stick to.

The Psychology of Comfort vs Opportunity

Markets punish indecision. When willingness is lower than ability, investors often build portfolios they can’t commit to emotionally. They start defensively, get jealous of rising markets, chase risk late, then retreat at the first sign of volatility.

This is not an investing strategy. It’s a behavioural trap.

On the flip side, investors with clear, aligned willingness and ability move deliberately. They know when to be bold, when to be patient, and when to do nothing. Their portfolios reflect strategy, not sentiment.

Case Study Logic (No Names Needed)

Consider two hypothetical investors with the same $100 million in capital.

- Investor A is well funded, long horizon, but extremely cautious. They sit heavily in cash and low-yield bonds. Over 10 years, their real purchasing power erodes. They sleep well but sacrifice upside.

- Investor B also has high capacity but is reckless, taking outsized bets on illiquid assets with leverage. When the cycle turns, liquidity vanishes, and losses crystallise.

- Investor C aligns willingness and ability. They take measured risk, manage liquidity prudently, and stick with their process through cycles. Their results compound quietly over time.

Investor C wins not because they’re smarter, but because they’re honest about who they are.

The Power of Strategic Alignment

In the end, markets don’t reward courage or caution in isolation. They reward consistency. Investors who build strategies they can live with through the entire market cycle tend to outperform those constantly at war with their own risk appetite.

If your ability is high but willingness is low, it may be worth questioning what’s holding you back. If willingness is high but ability is low, the portfolio needs to be restructured before reality does it for you.

This alignment is not static. As circumstances change, liquidity, goals, age, obligations, so too should risk willingness. A disciplined process revisits these questions regularly.

TAMIM Takeaway

Markets don’t reward the bold or the cautious. They reward those who know themselves.

Understanding your willingness to take risk is not an academic exercise. It is the foundation of a resilient investment strategy. Forecasting, valuation models, and macro narratives matter, but they all sit on top of this psychological and structural bedrock.

The investors who thrive are not those who avoid risk but those who own their relationship with it.