Hence we thought it might be pertinent to ask the following question: Does it make sense? Or is there something else at work?

In answering this, we can start with the premise that, on traditional metrics, this does seem to be a late-cycle phase. Fundamentals wise, we have seen the continual downward revisions in global growth and corporate profits (as the impact of tax cuts in the US wear off). When combined with escalating geopolitical tensions ranging from trade to the increasing potential for war (i.e. Iran) it does seem rather more prudent to go towards risk off. However, this does not seem to be happening and one of the key reasons behind this may be elsewhere from where the market is currently looking, we put forward the proposition that the reason behind this is a combination of low inflation, low interest rates and, biggest of all, changing demographics which is creating a secular bull thesis for both equities and bonds.

In essence, from our perspective markets are being driven primarily by liquidity and the search for yield at present. As the developed world’s population continues to age and the savings flow into pension and superannuation funds we could very well see the evolution of a high P/E market along with inflation across every asset class including fixed income, which continues to defy the logic of everyday market participants. So, whilst it would be easy to suggest that this latest upward trajectory is a melt-up we cannot be so certain.

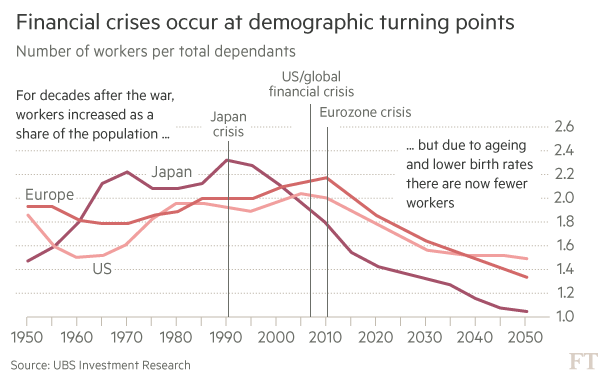

Perhaps one of the most under-researched and overlooked aspects of financial markets has been the precise impact of an ageing population on the composition of the markets. While there is the odd paper that looks at the broad macro-variables and the impact of an ageing population on productivity and underlying economic growth, the same cannot be said for its impact upon financial markets as well as the investment environment. This is especially concerning given that, as the below chart shows, demographics have been an exceptionally good predictor of crises in the past.

On an intuitive basis, the relationship is easy to understand using a simple life cycle logic. A person, let’s call them X, starts work in their 20’s typically. Their expenditure tends to exceed their income. They buy a house and, as they advance into their careers, their income will eventually reach a point where it will exceed the expenditures and, while the majority of their assets might still remain non-financial (property, vehicles etc.), the excess in income is typically put towards the accumulation of assets (often growth equities). As they continue to progress and hit retirement thresholds the asset allocation tends to be translated into income, usually through the use of annuity-like instruments or bonds, at which point a phenomenon called decumulation begins to occur. Savings are no longer prioritised, the focus is now on maintaining a certain lifestyle through a certain period of time. Now imagine a scenario where the replacement levels are continually on a downward trajectory whereby a growing proportion of the population is heading towards retirement and the working age population is shrinking. The first thing that tends to happen here is an increasing demand for bonds and annuities which put downward pressure on yields naturally and also leads to a steady decline in broadline savings rates (more decumulation) which gets worse as people live longer.

From a logical perspective, what do you get when there is less saving but growing demand for bonds (hint: it’s called leverage)? So herein lies our first point, there is already a secular demand for bonds and when combined with a lack of savings rates in the country, this tends to be a self-perpetuating cycle.

So then the next logical question from there would be to ask the question would be: as the population continues to age, does that mean that there is a bear case for equities? Going back to our person X, as he retires isn’t he likely to get rid of his equity assets and go towards less risky yield-based products?

Again, on an intuitive and arguably rational basis, this would be true. But consider a scenario where the central bank steps in and lowers interest rates toward the zero bound (doesn’t sound familiar at all, does it?), or even effectively crowd out private investors through QE. This would exacerbate the problem of demand and give further catalyst to bond prices, lowering yields across enough tranches that investors are forced to go towards riskier and riskier exposures (sub-investment grade) or go towards/stay in higher yielding equities. All this and the problem of leverage is exacerbated ever more seeing as there is next to no incentive to save in the system from whatever working-age population is left. On top of that, there is a further drive towards equities across all age groups again since the savings rate is zero bound.

Coming back to why equities have held steady besides the perceived risks in the system. The answer is that in the current environment any slow-down in corporate profits would have to be great enough to offset a close to zero cost of capital. In other words, if the risk-free rate of return (which we accept to be the yield on government bonds or long-dated T-bills) is 0, or in Europe’s case negative, then corporate profits would have to turn true negative in order for the markets to actually correct or they will hold relatively steady. Put another way, a mere slowdown in corporate profits isn’t actually going to lead to a correction since the alternative is no-return. We believe this aspect of the market is not likely to change anytime soon given the lack of inflationary pressures in the economy. As the old saying goes ‘you cannot fight the Fed’ or any central bank for that matter.This also might answer the question of why the negative correlations between bonds and equities have been broken in recent years. In an ideal world bonds would be safe-haven assets and a diversification tool, but in a world where there is enough artificial demand created through zero bound interest rates and ageing populations they will neither be a good predictor of what is to come nor will they be a diversifier (they will be exceptionally and increasingly correlated with equities and, given the amount of demand for risk assets, will be increasingly disconnected with fundamentals and economic reality). That being said, we have always said that GDP growth never really had anything to do with equity market returns or Zimbabwe and Rwanda should have some real winners.

Does that mean we are suggesting that investors should continue to be 100% invested in equities? Definitely not. Equities as an asset class will be the best performer over the long-run but, unfortunately, most people do not think in time horizons of 100 years. So, we would like to reiterate the importance of staying dynamic in your allocations. One of the key elements to think about when structuring your portfolio should always be the concept of Net Present Value (NPV) and opportunity cost. In a world where there is no benchmark for the risk-free rate of return, our life becomes a little more complicated. What should the discount rate be in this instance? We would suggest that this will have to be an increasingly arbitrary percentage based on the calculus of someone’s age and minimum requirements (translated into yield). For example, if you require AU$50,000 and your total asset base is AU$500,000 then your discount rate would have to be 10%. Please note the example used is for illustration purposes only, using a 10% discount rate would lead to some unexceptional risk-management.

In the medium-term investors are unfortunately left with little choice but to have a risk on trade constantly and central banks have very little wiggle room, through blunt policy instruments, to unravel the distortions existing in the system (hence further increasing leverage in the system) unless we want to go through substantial pain. We all saw how that turned out in Powell’s case, we hope that he won’t be demoted anytime soon.

In essence, this is likely to mean that equities remain the largest component of any portfolio. That said, we will also likely see a greater amount of volatility in the coming months following the G20 as trade tensions continue to escalate and supply chains continue to be recalibrated. One of the most interesting developments to watch will be whether these geopolitical pressures also create inflationary pressures (we haven’t seen it yet, but consumers in the US will eventually see the cost of tariffs passed through) as these supply chains undergo changes. Closer to home, the slowdown in global growth and the double whammy of a slowing property sector is certainly a significant headwind given our reliance on commodities exports. However there is a caveat, even if you were not particularly optimistic about global growth, Australian investors have a significant advantage over their global counterparts. The nature of AUD means that it is a natural hedge against the volatility of global markets. What we mean here is that, because of the nature of our currency and its correlation with commodities, our investments should be able to significantly outperform and withstand any headwinds (especially USD based investments). In a bear scenario money tends to find itself going to safe haven currencies like the Yen and the USD. In fact, Australian investors with global exposures would’ve seen significant outperformance as a result of currency exposures which will, for the foreseeable future, continue to be the case.Closer to home, even if there are headwinds in the overall economy, the government put remains in place just as it is globally, whether you agree with it or not (thank god for 3-year election cycles?). And though Mr Lowe has ruled out QE, something in us thinks that when push comes to shove…..