Guy Carson

Four weeks ago we wrote an article entitled Australian Banks: The death of a 25 year bull market, in which we looked at recent history and suggested that the tailwinds of lower interest rates and favourable regulation were over for the Big four banks. With regards to regulation, we focused on recent changes from APRA and the indication from that organisation that further measures were to come. What we didn’t expect at the time was action from the Federal government and to that regard we were surprised by the introduction of a bank levy in the 2017 Budget last week.

It is fair to say the banks were caught off guard as well by this move as well. In response the CEO’s of the big four have issued statements suggesting that the cost will be felt by “shareholders or customers” or perhaps a combination of both. The government hopes that the banks will not pass the increase on to customers, with Scott Morrison saying “The banks want to send a message to their customers about how much they value them? Don’t do what they may be contemplating doing [raising rates or reducing returns]. Don’t do it.” Therefore, the suggestion from the government is that shareholders wear the cost.

In order to determine who will feel the bank levy, it’s important to step back and to look at two things:

- What is the bank levy? How does it work?

- How might the banks react to this new charge?

What is the bank levy?

In order to understand how the bank levy works, it’s important to understand how banks are funded. The big four currently have leverage ratios of approximately 5% (ANZ 5.3%, CBA 4.9%, NAB 5.5%, WBC 5.3%), this effectively means they have leveraged their equity 20x and the remaining 95% of the balance sheet is funded by liabilities. It is these liabilities that the bank levy is set to target.

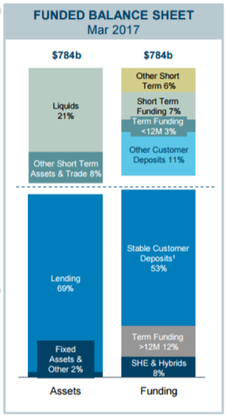

The levy applies to all bank funding outside of shareholders equity (including retained earnings) and deposits less than $250k. The below chart breaks down ANZ’s current balance sheet by both assets and funding source, it is the funding side that we need to focus on.

Roughly speaking, the Big 4 have balance sheets that are 10% funded by Shareholders Equity (SHE) and Hybrids, 60% funded by customer deposits and 30% by wholesale funding. The wholesale funding above is split into short term and term funding. These buckets are a product of capital markets and include instruments such as corporate bonds and commercial paper. These bonds are typically held by offshore institutions.

The levy is 6bp and is charged on the liabilities as identified above. To break it down further:

- The wholesale funding on the balance sheets of the big four will be subject to the levy, it’s impossible to avoid. So at a minimum 30% of their balance sheet will be subject to it.

- The equity component which ranges from 4.9% for CBA to 5.5% for NAB will not be subject to the levy. Note that the 8% number in the diagram from ANZ above includes hybrids which are subject to it. This potentially means less hybrid issuance going forward.

- The grey area is where the bulk of the funding comes from and that is deposits. A majority of the current deposit base is over $250k and is subject to the levy. How the banks react to this is potentially the key to who bares the cost of the levy.

How will the banks react?

The banks were caught off guard by the announcement of the levy and as a result we are yet to see any reaction outside of a few statements warning of the consequences. Therefore we’re not yet sure on what will happen but we can look at some hypothetical scenarios. The banks have indicated that the costs of the levy will be felt by “shareholders or customers”, we’d also add in a third category: staff.

Essentially we can see three ways the Australian banks may react:

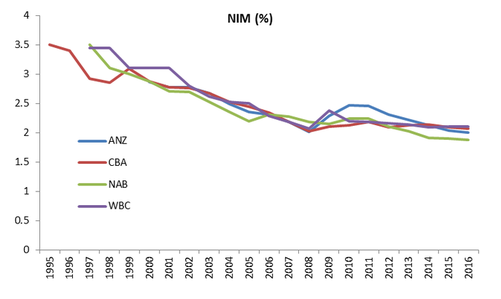

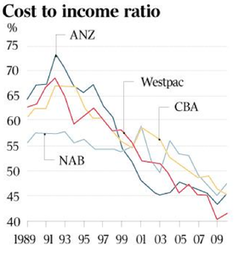

- Take the hit and see Net Interest Margins (NIM) reduce. Meanwhile try to offset the NIM impact by reducing staff numbers, improving productivity and lowering the cost to income ratio.

- Since deposits under $250k are now more attractive on a relative basis, the big four could increase Term Deposit rates for lower amounts and try to lock in funding that way.

- Increase interest rates for borrowers, most likely mortgage holders as that the bulk of their asset book.

We’ll start by looking at scenario one. The banks NIMs have been declining for over 20 years from levels of around 3.5% to 2.0% today.

Moving onto scenario two. In August last year, after the RBA cut interest rates we saw something unusual. The big banks all moved to increase term deposit rates. This lasted for about a month and was essentially a market share grab from the big four against the smaller players. Given the now relative attractiveness of smaller deposits, we may see something similar in the coming weeks. The flow on effect will be that players such as Bendigo Bank and Bank of Queensland will be forced to increase their rates to compete. Therefore funding costs across the industry will rise. Although it must be noted that the regionals will still have an advantage over the big four, as it is impossible for the big four banks to reprice their entire funding book. It is only the marginal flow that will be repriced which is a small aspect.

Rising funding costs brings us to scenario three and the pass through. If the big banks do successfully push marginal funding costs up across the industry, then mortgage rates will rise. This follows a recent trend of “out of cycle” rate rises. The interesting thing is that it is questionable, given high household debt, whether the economy can withstand increasing interest rates. As a consequence if rates do continue to rise, it raises the probability of further RBA cuts later this year.

Now these three scenarios are not mutually exclusive. Ultimately we’d expect all three to happen to some degree. Banks have been cutting costs for some time in the face of slower revenue growth, it can be expected this will continue. We expect there will some sort of market share grab with respect to Term Deposits in the not too distant future and in conjunction with that we might see a rise in interest rates for mortgage holders right across the industry. The combination of all three may still not be enough to absorb the levy and hence the prices of the Australian banks have fallen since its announcement.

So where does this leave us with respect to our view on the banks? In our recent piece, we noted that banks faced a risk of greater regulation and whilst we did not expect this levy, it is part of a greater trend. This levy therefore further reinforces our view that the best days in terms of share price performance are behind them.

Finally, we do note that the recent history of the Australian government is not great with regards to market timing. In 2012, the then Labour government signalled the end of the mining boom when they introduced the mining tax. Has this Liberal government’s 2017 Budget managed to do the same with the banking boom?