Author: Sid Ruttala

Before we begin, a quick recap of the main points from last week:

- Over the past few decades the industry has been characterised by exponential declines in overall IRRs for new products;

- The above scenario can be attributed mainly to increased regulatory and compliance requirements which have incentivised massive consolidation in the space along with greater focus on maximizing the potential monetisation of existing patents;

- This is despite the fact that in nominal terms global biopharmaceutical R&D expenditures continue to be an outlier in comparison to even the defence and software sectors. This can mainly be attributed to significant cost increases as opposed to real growth though.

- Finally, this has also created certain unique characteristics such as public, private and academia collaborations (most recently seen in the development of the Covid Vaccines) as well as success stories such as India which has become the powerhouse when it comes to manufacturing capacity and generics.

At this point, many may be arriving at the conclusion that this seems to be an argument against investing into pharma. So, why then do we feel that this is one sector that may have legs? We shall begin by returning to our base case scenario around inflation and rationalise why pharma, and biotech in particular, makes sense.

Think for a moment about a company that is undertaking R&D. Given what we just mentioned around associated costs, it is likely that a significant proportion of their financing comes via the issuance of debt (rarely is it the case that, outside of the majors, biotech companies in their infancy have positive cash flows). Similar to our thesis around listed property, issuing debt, especially longer duration and locking in rates, is effectively a transfer of wealth away from debt holders to equity holders. Moreover, once a firm passes from the R&D stage to actual commercialisation (assuming that it doesn’t make itself a takeover target, consolidation is a hallmark of modern pharma), this effectively creates a double tailwind for equities investors.

Let’s also consider the actual attributes of intellectual property in this particular instance. IP protections effectively ensure that no one else can compete against a particular product line for a given period. In real terms this means it is behaving the same way and has the same scarcity value attributes of precious metals. In effect, if inflation is rising then a seller (of IP) just adapts the asking price and valuation in a much more fluid manner than would otherwise be the case.

Last but not least, the attribute that is most prominent and which most people may be aware of is the inelasticity of demand. That is the change in quantity demanded in relation to the price. In the absence of regulatory intervention and assuming patent protection (which is effectively the highest barrier to entry imaginable), healthcare expenditure is potentially the best inflation hedge possible. In fact, one favourite piece of research is one conducted by Mark Hulbert which showcases that healthcare beats any other industry, including the gold miners or bullion which most people are familiar with. The logic is rather intuitive. With the exception of elective procedures, consumers don’t have the opportunity to turn down medical care because of price increases. The most infamous recent example of this being Martin Shkreli (currently in prison for securities fraud), hiking the price of a life saving AIDS drug from $13.50 to $750 in 2015. Consider the nominal increase in medical care expenditure since 1948, the multiple increase over the period is 40x while the increase in official CPI over the same period is 12x.

But what if we’re wrong about inflation? A rather valid and pertinent question to ask. Even here, we feel that recent events have presented a turning point for the industry overall. Covid has shone the limelight on just how global and interconnected supply chains have become. Take the policy response in India which, as previously alluded to, manufactures approximately 50% of the global vaccine supply. The bipolar response of the central government which, much like the Trump administration Stateside, continued to hold election campaigns and enabled religious festivals (after taking a stellar initial response). The flip side of this scenario was that the second wave of the virus effectively crippled that nation’s ability to export its vaccine supply (which many emerging markets were relying on). The point here? We will likely see increased government support to subsidise and reshore certain manufacturing capacity. A certain tailwind, especially for the consolidated top end (including Pfizer which we spoke of last week).

Sticking with the topic of viruses and vaccines, resistance to second and third-line antibiotics is expected to be around 70% higher in 2030 (compared to 2005 in OECD countries). This, combined with a lack of new drugs and patents, will create a catalyst for the sector going forward. In essence, Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) will, even on conservative modelling, result in the death of approximately 10m people p.a. globally if current approval trends and increases in resistance exceed approvals. This creates another tailwind, not only in increasing regulatory efficiency for, if Covid has proven anything, it can be rather more efficient and timely in the presence of emergencies. Using current trends, even with AMRs, we are headed towards one.

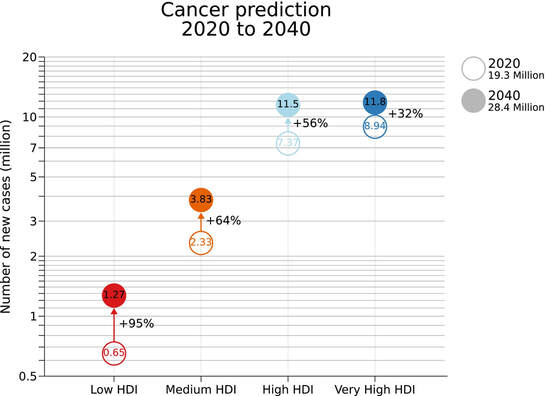

Moving away from vaccines, some interesting and lucrative trends that are likely to play an increasingly prominent role are diabetes, oncology (cancer) and cardiovascular/respiratory, all of which we feel will continue to grow at exponential rates globally. On the first front, the changing eating patterns in emerging markets, incorporating more processed food and foods higher in sugar and salt, ensure that we should see a double digit growth when it comes to the diabetes segment. India, for example, is expected to roughly double its diabetic population between 2017 and 2025, from approximately 72m cases to 134m. According to the International Diabetes Foundation in 2019, “approximately 463 million adults (20-79 years) were living with diabetes; by 2045 this will rise to 700 million.” In an amusing yet somewhat twisted example of capitalism, “Nestlé would sell a problem with one hand and a remedy with the other”. With, amongst other things, their Nestlé Institute of Health Sciences, they are both enabling and profiting from the problem but also looking to enter the market for the treatment.

So, let’s sum up some key attributes that investors should look for given what we have covered so far:

- Look for companies with significant patent protections and ones that operate in markets that have less regulatory intervention when it comes to pricing. In markets such as Australia or the EU, an interesting angle may be to find companies with organ drug designations. These patents protect companies that go after rare diseases and give longer term protection. One company owned personally is Neuren Pharmaceuticals (NEU.ASX) which has an interesting pipeline targeting Rett Syndrome and Fragile X, both rare but significantly debilitating conditions for adolescents. If the company does succeed in trials, it will have 7 years of exclusivity in the US, for example, in the distribution and marketing of these drugs.

- Look at the duration and nature of the debt on the balance sheet in conjunction with the nature of the eventual revenues. Moderna (MRNA.NASDAQ, owned), for example, continues to hold US $603m, a figure substantially higher than its counterparts in biotech. But, assuming it continues to hold its revenue run rate, this should not be an issue. Though the same cannot be said for its valuation at US $93.4bn, which seemingly prices it for perfection. Despite this, I continue to hold personally given their exposure to MrNA therapeutics in the Oncology and Cardiovascular categories.

- Stick to the more lucrative categories of Oncology, Diabetes and Cardiovascular. These categories are not only relevant due to the number of people they impact but because of the nature of the markets they are prevalent in which remain lucrative. So, while viruses such as HIV may still have a massive impact on emerging economies and vast swathes of the global population, especially Africa, the ability to price is quite limited. Put another way, cancer’s continued prevalence in developed markets makes it a margins game whereas diabetes and cardiovascular is both margins and growth. That is, greater pricing power combined with volume growth in markets such as India and South East Asia. Some personal favourites: Fate Therapeutics (FATE.NASDAQ, owned) for oncology, DexCom (DXCM.NASDAQ, owned) for diabetes, Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMY.NYSE) for cardiovascular.

- Outside of the three aforementioned categories, there is also much to be said for generics manufacturers who are able to get licensing agreements and scale across emerging markets. Here we are looking at not particularly high margins but great growth potential. Some firms that remain interesting are Sun Pharma (SUNPHARMA.NSE, owned), Lupin Pharmaceuticals (LUPIN.NSE, owned), Biocon (BIOCON.NSE, owned) and Cipla (CIPLA.NSE, owned). All of these working across the lucrative categories but playing the lower cost and poorer markets.

Next week we take a more in-depth dive into a number of the aforementioned companies including Moderna, Fate Therapeutics, DexCom and Bristol-Myers Squibb. Following which we shall conclude with a few of the generics manufacturers.