What Really Matters in Investing22/6/2023 The world of investing can be a complex and ever-changing landscape, and the financial media can make it even more confusing, having you believe that the macroeconomic news of the day is the most important factor in any of your investing decisions. Yet the overwhelming majority of the world’s greatest investors disagree. Legendary high-yield bond investor and billionaire Howard Marks is one, and his incredibly insightful memos to Oaktree Capital clients contain infinitely more valuable investing wisdom than the daily newspaper. His 2022 memo What Really Matters in Investing is one such treasure trove, offering a roadmap to successful investing.

Macro MattersOver the past 12 months, interest rates have increased at the fastest pace since the 1980s in both Australia and the United States (they’ve also risen dramatically in Europe and the United Kingdom). This has captivated the financial media, with a near-endless stream of articles about how this affects consumers’ cost of living, house prices, and other financial markets. With the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA) meeting on the first Tuesday of every month and the Federal Open Markets Committee (FOMC) meeting 8 times per year, there is always plenty to discuss about the next rate decision (or even the minutes of the previous session). Any decision that differs from “expectations” can have a dramatic impact on the stock market, or even currencies–as you can see from the drop in the Australian Dollar on Tuesday this week. We saw this in June, when the RBA lifted the cash rate by 25 basis points (0.25%) to 4.1%. The majority of economists had predicted a “pause” and this had been “priced into markets.” In justifying the decision, RBA Governor Phillip Lowe referenced still-high inflation: “Inflation in Australia has passed its peak, but at 7 per cent is still too high and it will be some time yet before it is back in the target range.” The FOMC, on the other hand, chose to take its first pause last week, with the Federal Funds Rate remaining at between 5.00% and 5.25%. This came as inflation had cooled in May to 4%, its lowest since April 2021 and less than half the peak of 9.1% this time last year. The FOMC left the door open for future increases however, depending on further reductions in the inflation rate towards the 2% target. Interpreting the comments made by central bankers has become almost a sport for pundits and the financial media, including measures like overlaying transcripts of the meetings to look for discrepancies and requesting additional Q&A press conferences to further explain the decision-making process. The tone, body language, or any other possible indicators are used to see whether the future path of interest rates can be predicted. But does it all matter?

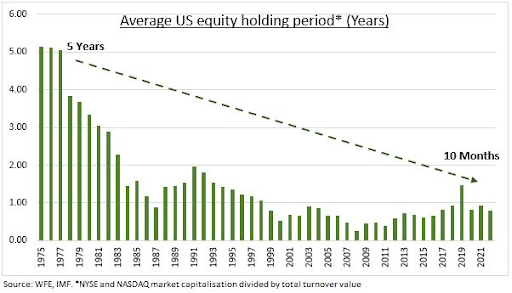

What Really MattersDoes obsessing over these monthly interest rate decisions actually matter to the extent the financial media would have you believe? A number of successful investors think not. In his 2022 memo to clients What Really Matters, Howard Marks explores the factors that he believes are important to successful investing results. According to Marks, investors fail to predict macroeconomic events and have even less success predicting the market’s reaction to them. Even more importantly, investors find it nearly impossible to accurately predict both macroeconomic events and their outcomes on a consistent basis (even the world’s best economists fail to do this, which has led to the famous quote: “economists have predicted nine out of the last five recessions”). Investors might get lucky once or twice, and this can often lead to fame in the financial media (Michael Burry has received a great deal of publicity for his success in shorting housing during the Global Financial Crisis, as portrayed in the film “The Big Short”). But there’s very little chance that an investor (no matter how intelligent or experienced) can successfully predict macroeconomic events and their outcomes on a regular basis. Marks also wrote about the trading mentality that’s becoming perverse in today’s investing landscape. Investors have increasingly come to view stocks as a tool for generating short-term profits, rather than ownership in a business. This can be seen from the average holding period of individual stocks in the U.S., which is now just 10 months (!), down from 5 years back in the 1970s. Marks advocates that investors overcome this mindset and only buy shares in businesses they wish to own for the long-term.

This is the same as advice from investing juggernaut Warren Buffett, who once told CNBC “Nobody buys a farm based on whether they think it’s going to rain next year…they buy it because they think it’s going to be a good investment over the next 10 or 20 years”. Practising what he preaches, Buffett outlined the success of long-term holding Coca-Cola (which he has owned since 1988) in this year’s Berkshire Hathaway Letter to Shareholders. Marks also wrote about volatility, pointing out the importance of being able to (emotionally) tolerate large market swings. This is again consistent with Buffett, who was once quoted as saying “We prefer a lumpy 15% return to a smooth 12% return.” By this Bufffett meant that he was focused on the end result (the investment’s total return) and not whether or how much it fluctuated along the way.

Memos over Media and Knowledge over NoiseIt’s easy to get caught up in the market news of the day. It’s hard to avoid the headlines and the media is skilled at grabbing readers’ attention. Timeless investment principles provided by investors such as Marks and Buffett seem less immediate and less sexy, and there always seem reasons to ignore them in favour of the current macroeconomic developments. Yet just like eating vegetables and regular exercise, they are a proven method for generating long-term investing success. Interest rates are a prime example. As Chris Mayer from Woodlock House points out in his most recent memo “The Wisdom of K”:

So, next time you find yourself reacting emotionally to the hot financial news of the day, perhaps turn your attention to a Howard Marks memo instead.

|