Investing internationally can expose you to currency risk. If the AUD$ falls against other currencies then you benefit to the extent that the value of your investment rises when translated back into AUD$. On the other hand if the AUD$ rises then the value of your investment is reduced by the extent of the decrease in the foreign currency. It is important to note that you haven’t lost money if you do not sell the position. It is only a “loss’ or ‘gain’ on the basis of adjusting prices to current market values.

Currencies fluctuate and in the short run can do so for random and illogical reasons. In the long run (5 years +) they tend to follow a more logical path which is determined by relative competitiveness in traded goods. Countries with more debt, more inflation, and less capital investment tend to have currencies which structurally decline in value.

The AUD$ has recently risen by about 5% against the US$ and the global equity portfolio has about 50% of its assets in US$ denominated stocks. This has reduced the value of the portfolio.

We consider below the reason for the increase and, more importantly, if it will it continue. Are we going to see a repeat of the commodity boom from China which drove the AUD$ over parity, and at the time caused all sorts of currency experts to predict that the AUD$ would remain there! As we said – currencies fluctuate in the short run and are notoriously hard to predict.

While equity prices could be said to behave in a predictably irrational fashion, currencies tend to behave in an unpredictability irrational fashion.

So what happened and why do we think this is nothing to worry about? You shouldn’t sell international equities nor be afraid of owning many foreign currencies.

- The RBA’s Deputy Governor successfully (sort of) arrested the Australian dollar’s ascent last Friday, but while it has at least stopped rising for now, its recent surge has not been reversed as it laps at 80 US cents and 5.4 Chinese renminbi (yuan).

- The US$ was faltering after a strong run as part of the ‘Trump trade’. Political gridlock in Washington (aka chaos) has removed some of the lure of the US$ and the big increase in infrastructure debt issuance at higher interest rates, now looks less likely.

- The Federal Reserve is once again signalling a slow exit from zero interest rate policy and only gradual increases in interest rates. The Federal Reserve, like all central banks, is keen to keep hinting to the market what they will do and is consequently causing the volatility.

- As economic news varies between a faltering USA economy and a strengthening USA economy, the US$ rises and falls with expectations of interest rate changes. In the Northern Hemisphere Summer, USA economic activity tends to be softer. Although seasonal adjustments are made in the measurement of these statistics, they are imprecise.

- The RBA Board meeting minutes released recently indicated the Board viewed the neutral cash rate as around 3½% compared to a current rate of 1.5%. This was (incorrectly) taken as a hint that rates would shortly be on their way there.

- The iron pre price in US$ has bounced which helps the AUD$.

Why do we think this is a temporary surge and one should remain invested in unhedged international equities?

- The last thing the RBA wants is a rising AUD$. it continues to acknowledge that …“An appreciating exchange rate would complicate” the transition of the national economy away from its earlier heavy reliance on the construction of big-ticket resource projects.

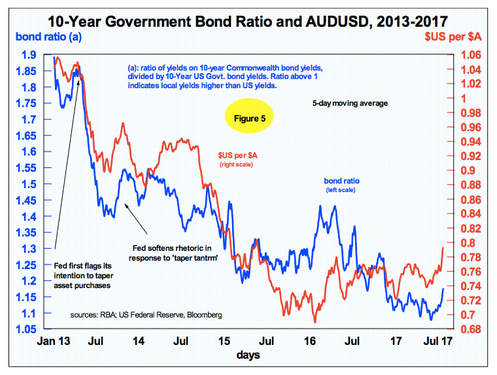

- USA inflation, or many components of the index, remains well-contained, and so the RBA’s capacity to switch back to a tightening bias, much less actually raise the cash rate, is limited by the extent to which they want Australian interest rates to be a lot higher than USA interest rates. We show the spread in the chart below. We are at an extreme now and a wider spread is not helpful to a smooth economic transition.

- Export item prices other than iron ore are still subdued. Note also that Chinese GDP composition will be different in the next 15 years from the last 15 years. In the last 15 years there was a lot of construction and basic infrastructure. As the economy matures there will be more services and less physical construction. To view Chinese GDP as being a predictor of commodity demand may no longer be quite as easy and analysts will have to be cognisant of this changing shift rather than simply measure the rate of Chinese GDP.

Most importantly the AUD$ is not a cheap currency. The OECD calculation of the PPP fair value of the A$, an anchor price around which news flow drives it up and down, is about $0.71. We attach that chart below.