Author: Sid Ruttala

Wherever you stand on the subject, and I shall avoid going into the science of climate change and the efficacy of the research behind it, these policy changes are happening. What we have been presented with is the certainty that there is general consensus towards creating sustainable goals and a key aspect of this is certainly the electrification of transport. However, when we talk of electrification we are not just referring to the electrification of automobiles but also large scale transportation including rail.

Let me set the scene, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA) and assuming a business-as-usual scenario, the demand for the passenger vehicle fleet will need to double to 1.7bn by 2035 and triple by 2050 in order to sustain even a modest amount of global growth. This increase comes at precisely the time when governments across the planet set out towards ambitious goals to diversify their energy base and reduce emissions. Regarding this, the EU has placed a reduction in emissions of close to 40%, China and carbon neutrality by 2060 and the US targeting reductions of 26-28% by 2025. This places immense pressure on both the automotive sector and the R&D race. This scenario makes electrification not only a “want” but a “need”, vital for the survival of auto manufacturers. This is because even if the average efficiency of the combustion engine were to be doubled it would not only be unable to meet the increased demand but also, from a regulatory perspective, meet emissions reduction targets (a double whammy).

To put this into a little more context, the world’s current stock of cars, trucks, buses, two-wheelers, trains, ships and aeroplanes account for about 20% of all primary energy consumed, almost 93% of which is dependent upon fossil fuels. Given that this is the case, there is a marked incentive for nations with a high level of population growth to diversify their energy supply, especially across Southeast Asia and much of APAC. This is perhaps the primary reason why the CCP decided to set up ambitious targets. It is not simply a question of emissions but also energy independence and national security. China and much of Asia is not only dependent upon fossil fuels but broader macroeconomic policy remains at the whims of energy prices. Take India as an example, its demand for energy is set to outpace domestic supply which, according to DFAT, will probably contribute less than 30% of that nations energy mix by 2035. It’s marked incentive is to diversify away from fossil fuels, including thermal coal which it remains on track to be self-sufficient in the medium term. From a policy perspective, this makes it imperative for Delhi to commercialise electric vehicles as quickly as possible.

What does this require?

One of the most misconstrued notions about the electric vehicle (EV) market is that it can be self-defeating in the sense that the source of the electricity generated might remain as fossil fuel. This requires a little more nuance. One interesting study I came across was a case study using British Columbia, where a renewable energy penetration target of 93% is set. Through the course of the study including scenarios making the utility controlled charging of vehicles to supply and demand. It showcased that electrifying the entire road vehicle fleet would require increased generation of up to 60% (relative to without electrification), though levelling the total cost of electricity at an increase of 9%. There are several angles to this study including the use of low-cost generation options such as wind and solar, as well as showcasing that the energy target would reduce carbon abatement costs by up to 30%. Further use of utility controlled charging actually reduces total system capacity up to 7%.

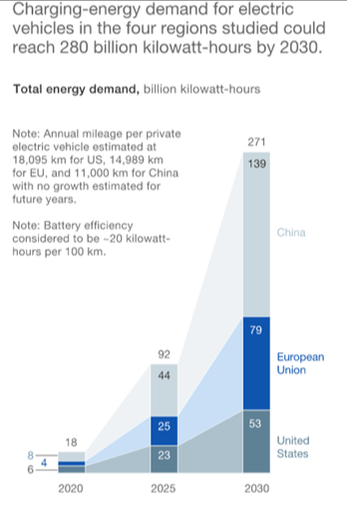

What is required if one were to extend the premise of that study to a global scale however is the necessity of a massive outlay in global infrastructure, not only in terms of charging stations but also increased R&D into battery efficiency. Without these outlays, large penetration of new technologies could have a detrimental impact upon grid operations and issues pertaining to excess generation, lack of flexibilities with the other headache being increased localised peak demands. This brings us to the first requirement, the building up of viable charging infrastructure and broader grid infrastructure that enables this while also maintaining current requirements for managing peak times. Take a look at the below graph which showcases the exponential growth in power generation requirements to over 280bn kilowatt-hours by 2030. The below scenario and assumptions bring us to the second requirement, that is innovation. In particular, the battery efficiency assumptions which are capped at 20 kilowatt-hours per 100km. From an investors perspective, there are two angles to look at here. The first is to find companies that are at the forefront in terms building out infrastructure capacity including incumbents, such as Royal Dutch Shell which recently beat expectations on dividend payout but is also looking to pursue its growing electricity business or traditional utilities businesses with a renewable energy mix. The second angle is to find companies that are actively seeking to increase battery efficiency, this might not necessarily be even the auto manufacturers, such as Tesla (TSLA.NASDAQ), but also companies like LG Chem (051910.KRX), Hefei Guoxuan High-tech Power Energy Co., Ltd (a subsidiary of Guoxuan High-tech, 002074.SHE), Contemporary Amperex Technology (300750.SHE), Samsung SDI (006400.KRX), Microvast (a pre-IPO company headquartered in Texas) to name a few that come to mind.

Now that we have the infrastructure and battery efficiency covered, it is time to move on to the inputs. Most people think of materials including lithium or copper. What is perhaps more pertinent to look at are niches including red-flags and companies actively seeking to target these. For example, traditional battery technology (i.e. lithium-ion batteries) are cobalt-based. This system consists of a cobalt oxide positive electrode (cathode) and graphite carbon (anode). This in itself creates a constraint of sorts, since 60% of the global supply of Cobalt comes from the Congo, more specifically the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), which has been historically unstable and the extractive industries are themselves prone to gross abuses including the use of child labour. Investors could then seek to identify companies like Novonix (NVX.ASX), which is actively seeking to produce and commercialise cathodes that are purely lithium-based without the use of cobalt.

On a global level, it would pay for investors to look towards companies who can dominate a particular niche within the manufacturing ecosystem, including semi-conductor and GreenPower subsets. GreenPower, for those of you unaware, is “a subset of renewable energy and represents those renewable energy resources and technologies that provide the highest environmental benefit. The U.S. voluntary market defines green power as electricity produced from solar, wind, geothermal, biogas, eligible biomass, and low-impact small hydroelectric sources” (Source: EPA).

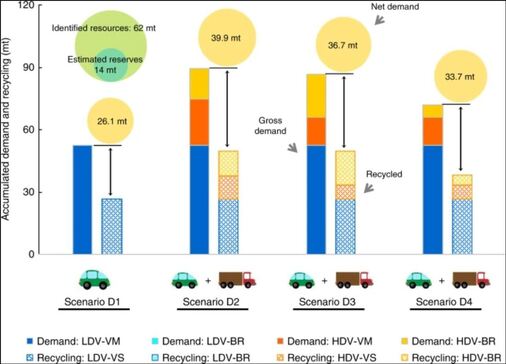

For the more adventurous (and those willing to stomach the volatility), the more traditional primary materials offer some exposure to the electrification trend, including lithium and graphite. I believe that current lithium prices should have considerable upside since most demand-based scenarios are predicated upon an undue focus on light-duty vehicles, with the assumption that the technologies underpinning the EV market will not be able to target the heavier duty large haulage market. One study I came across, by Han et al., showcased that mass electrification of the heavy-duty segment on top of the light-duty would substantially increase lithium demand and impose an immense strain on global lithium supply. A result that is attributed to the large single-vehicle battery capacity required by heavy-duty vehicles and the required increased replacement requirements. Under the above scenario, the net demand (including recycled) goes to about 38.9m metric tonnes, with current proven reserves stacking up at 62m. However, even here investors must remain cognizant of the interconnectedness of this to battery efficiency and broader technological advances taking place (i.e. higher the battery efficiency, the lower the replacement and hence lower demand for lithium).

There are many ways to play the electrification of transport aside from the simple headline-hogging automakers. One should take a look at the relevant supply chains and adjacent categories, there are hundreds of possibilities here. There is also geographic segmentation to consider and one must take a look at some of the Asian markets for this or risk missing out. Don’t forget to look at the niche players out there that can target specific red flags too. This is still just the beginning but one thing is for sure, this thematic is going to produce some real returns for the savvy investor over the next decade.