We have previously stated that we view the trade war as not necessarily a question of simple economics or ongoing Current Account Deficits. In fact, we are of the opinion that as long as the USD remains the global reserve currency, the artificial demand created by global trade effectively ensures that the US could at least theoretically maintain such deficits for an indefinite period of time without being too adversely impacted (hopefully we don’t have any workers from the American Midwest or Rust Belt reading this). Quite on the contrary, we view this current adversarial environment as a longer-term trend that will take us slowly but surely towards a new equilibrium in the global economic order. One outcome of this is that the two major players (the US & China) increasingly look at disentangling their supply chains and carving up spheres of influence. All this in preparation for an era where the very essence of political and economic survival will be contingent upon leadership in the next generation of technological advances broadly characterised as the fourth industrial revolution. The clearest and most obvious representation of this process has been the curious story of Huawei.

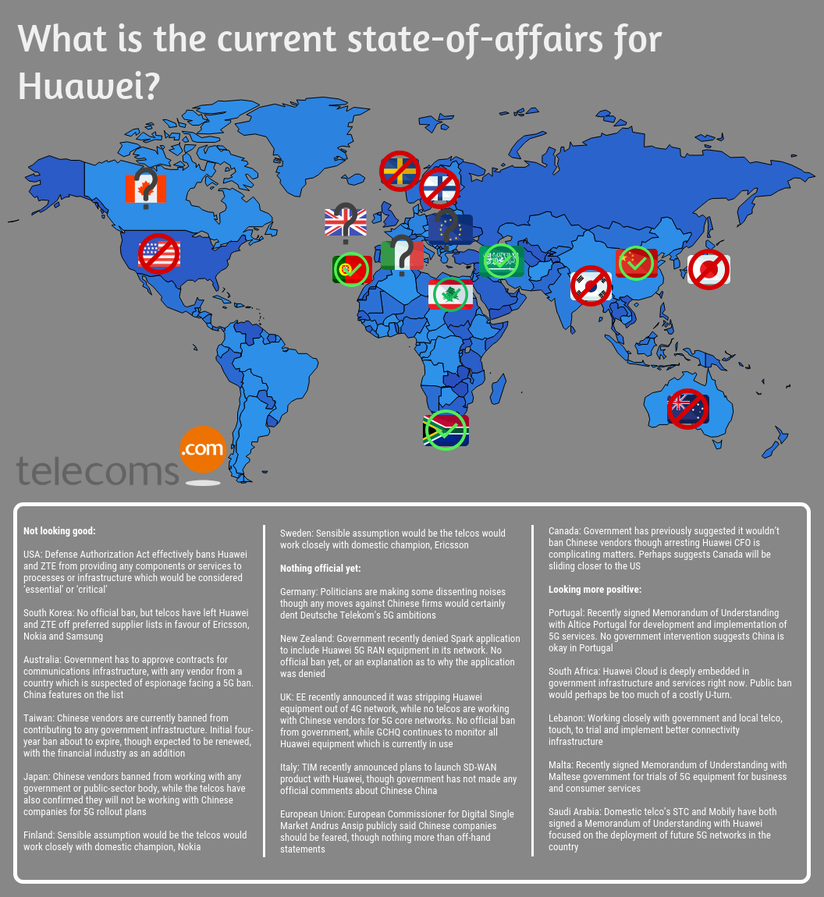

The recent headlines surrounding this rather opaque company made us want to take a closer look at it. It has certainly been a busy time for them on all fronts and we think their PR teams might be having a more interesting time than those in the White House in terms of putting out fires on an almost daily basis. From mere accusations by the US administration to the State Department making it official policy to intentionally go out of their way in convincing governments around the world to view them as a threat, lobbying heavily to block their usage in the rollout of 5G in the UK and across the EU.

Closer to home, state and intelligence officials continue to persuade our own government to view Huawei increasingly as a proxy for the Chinese State. Whatever the truth of the matter is, and we feel somewhat disposed to believe that there may be an element of truth in the accusations, we might then ask ourselves the question, just why is it that there has been such a furor created about this one company? To the point where individuals are being caught in the crossfire, the most immediately obvious case being the arrest of Meng Wanzhou, CFO and daughter of the companies founder, in Canada for breaking US sanctions against Iran. Officially the US Attorney’s office where the warrant originated is nominally independent, we remain unconvinced that the White House would not be at least given a heads up before the US Attorney for the Southern District went ahead and issued it though. We get the feeling that, if not for the fact that she was the daughter of the founder of Huawei and the granddaughter (on her mother’s side) of a Deputy Governor of Sichuan (her father having married particularly well), things might’ve been rather different in ages gone by. A slap on the wrist, a few outraged interviews and the world would’ve moved on. We’re not legal professionals but a slight bureaucratic delay in the issuance of the extradition request until Ms. Meng was back on Chinese soil would’ve done it. After all, when there is a will there is a bureaucratic hurdle in the way.

Cynical? Remember Jamal Kashoggi? Sadly, probably not. Popular conscience seems to have the memory of a goldfish.

The very fact that there seems to be an increased propensity by both parties to dig themselves in quite hard tells you all you need to know, at the very least, about the importance of control over 5G and the global communications landscape/infrastructure for both governments.

The argument over Huawei’s opaque ownership structure and extraordinary closeness to Party officials are certainly red flags. This in itself shouldn’t be an issue altogether based on past behaviour though. If it were, it would essentially preclude us doing business with a large chunk of Chinese corporates. As we have previously written about, opaque structures and closeness to government officials is a norm rather than an exception in China. In addition, Huawei’s ability to garner local government contracts and scale operations on a rapid scale was actually what attracted US companies like 3Com and Symantec to partner with them in China in the first place. We have also previously elaborated on the eventual issues that foreign partners have had in sectors ranging from automotive to financial services (for further reference please look to the case of SAIC and GM in Shanghai). What is the distinguishing feature here is the sheer amount of friction this has caused on both a geopolitical and international front.

We think this might have more to do with how much of a threat the company itself, and the new economic footprint that the CCP has undertaken, poses to US commercial interests. The argument we make is that, as Huawei and other Chinese companies move further up the value chain (as opposed to basic manufacturing), this is inevitable. We have seen this story play out in the past, just look to Japan in the late 20th century. Similar rhetoric was used in pointing out the opaqueness of Japanese Keiretsu firms and the unfair advantages that said companies had in trade. Initially, in the US, governments and regulators alike were happy to see what was essentially labor arbitrage. They can no longer do so now as the Chinese economy has transitioned to middle income. In order to sustain growth levels and avoid the middle income trap/secular stagnation, the economy can no longer rely on cheap labor as the primary driver of corporate investment. The Chinese state’s solution to this conundrum poses a direct threat to high-tech US firms and Silicon Valley’s almost hegemony-like status.

Ironically, the vitriolic rhetoric of the Trump administration may have had the benefit of giving the Communist Party its catalyst to make some rather painful transitions domestically as the issue is now one intrinsically tied to issues of national pride. As we like to say, nationalism goes both ways. It gives the excuse that Beijing needed in order to build consensus and undertake the rather painful reforms. The inevitable slow-down and short term pain that comes from a rapid shift in policy settings as they make the transition towards consumption led growth and higher value add services/manufacturing can always be blamed on external forces (for example, quiet factory floors in places like Shenzhen and a ticking up of unemployment). The most obvious sign of this has been the increased tendency of Chinese consumers, especially in the younger generation, to dispense with buying iPhones in favour of local brands such as Huawei. The latest trend has been to build an app store that is a viable alternative to the Android or iOS based platforms.

We do not claim to have a crystal ball that predicts who might end up winning in this race. But from Huawei’s perspective we think they have a marked advantage in many ways. For one thing, they are not driven by the same motivations as listed companies in the US or notions of shorter term profitability, not to mention the significant amount of cash that Huawei has retained on the balance sheet.The global communications supply chain is very interlinked as companies have increasingly looked to specialise. So, in essence, companies that might compete in one market might act as customers and suppliers in others. The blockage of US companies from doing business with Huawei will make consumers worse off in the short run at least. For one, Huawei has a proven record of efficiently and effectively building out network infrastructure, though they do rely on certain components from US companies for this. The ban will have the short term impact of slowing down the process of 5G rollout around the world and increase the associated costs. For telco providers such as Optus (Singtel), this will make things increasingly complicated, being caught in the crossfire, since they have to work around relationships with their US partners while still maintaining pre-existing strategic partnerships with Huawei (including things like their joint research center).

On a longer term basis, this will effectively create two distinct opportunities to benefit from. First, the creation of artificial regulatory barriers can actually be beneficial for incumbents as it can insulate them from competition. That being said, the increased competition from new greenfield markets might put downward pressure on margins over the long term but we think the insulation might be good for margins in the medium term. Rather than product segmentation our view is geographic segmentation will become increasingly important. So then the true target and playing field will be greenfield territories especially emerging markets across South America, South East Asia and Europe. These areas will be where Huawei and its American counterparts go head to head in a battle for dominance. With some insulation in terms of their existing foothold in domestic markets.

From a corporate perspective we will start by saying that we doubt Huawei will ever go public. Even the legendary founder Ren Zenghfei officially only owns 1.5% of the actual company, the rest of the ownership held through a series of opaque structures that give some credence to the suspicion of effective control by the Party. However what will be interesting for investors will be the implications that the regulatory environment creates for others across southeast Asia, including Taiwan. Said players will be beneficiaries through Huawei’s largess and their need to source alternatives in terms of hardware and supply chain replacements (some profitable opportunities to be had thanks to an acquisitive giant mayhaps?).Another strategy being touted is the potential for Huawei to open its software architecture and turn it into open source. They may also find themselves giving away certain technologies to partners that might be able to roll out in the US thus circumventing any sanctions. This will, we hope, be an interesting longer term trend and something they might look to achieve in pursuit of both positive synergies from an ideation perspective as well as a competitive ploy.

On the flip-side, Huawei’s closed and rather opaque governance mechanisms will also be a hurdle to further scalability in the wholesale market. This will be where politics will certainly come to play, with increased lobbying on an intergovernmental playing the prominent role. For example, the Chinese government might give certain incentives or parcel certain projects as part of the OBOR initiative in Central Asia.

We however doubt that the governance structure is going to change though even if it is profitable in the short-run and allay concerns from global regulators. This isn’t all about money after all, as any person who has followed Mr Zhengfei can attest. With his obsession for Napoleon and a penchant for European military art, we think this might not just be about profit. After all, here is a man who from humble beginnings as a researcher in the PLA (People’s Liberation Army) has built a global behemoth. For those of you unaware, he started very much as the perennial outsider, his family coming from a Koumintong background and being distrusted by Party Officials (which precluded him from joining its apparatus for a significant period of his life). He grew leaps and bounds by managing the officials in mutually beneficial manner as well as making himself useful by building up the nations capabilities in strategic sectors. With the new generation of Party Leadership being dominated by previously untouchable outsiders we think things will get a lot more conducive for him and he will play a vital role in the future of China’s commercial policy. This is mere speculation, but we somehow doubt his interests might be driven by purely commercial motives, in him we see a pragmatic individual intent on building a legacy. This aspect of his personality would certainly explain his hobbies and fascination for that other upstart conqueror in history.

But who are we to judge, we have our very own conquering types. The longest standing of these would be the infamous Rupert Murdoch brigade. In this instance all we can do is figure out places where we might pick up some profits in the fringes as they go about their process of Empire Building.

(as we said, that penchant and fascination with European conquerers/imperial era styles is very real judging from the campuses alone)