We begin this weeks article on global debt with a story. This is the story of Sri Lanka which has seen and continues to see significant turmoil driven in no small part by their government embarking on a series of reckless fiscal spending measures over decades. While this was ostensibly blamed on the Covid crisis, a little investigation reveals a multi-decade story of populist measures, reckless tax cuts (not accounted for), and indebtedness to foreign powers, including China. What are the results? A government that has finally realised that it is not able to meet its basic obligations, civil unrest, the resignation of a Prime Minister and cabinet with an embattled head of state unable to dig himself out of a hole. Take a step back and one can see this story starting to play out on a much grander scale.

Think Latin America, emerging markets in Africa and across South East Asia. So, why is this an issue now? Well, unprecedented Covid-related measures have seen this peak. As the US Fed reverses course after decades of largesse (along with the ECB), we see the other impact of rising interest rates; increased debt servicing costs. This is likely to lead to austerity.

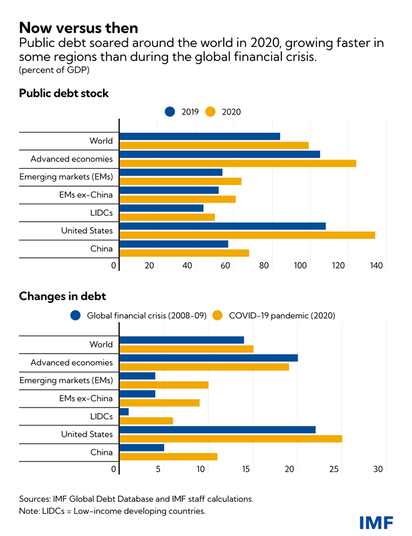

2020 marked the largest one-year debt surge since WWII, Global public debt rising to approx. US $226tn (global GDP was $94.935tn in 2021). Was this Covid and was it inevitable?

Looking at the rationale for government expenditure, current wisdom (decidedly Keynsian) formulated following the Great Depression asked a simple question: Can governments intervene to smooth out business cycles and, if so, how? The solution posited is simple, save during good times via increased tax receipts and budget balance, which allows the economy to not overheat and consequently cause inflation, while the converse is true during recessionary periods. Expenditure in this sense implies creating money supply in whatever form, the famous quote in Keynes’ General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money is:

|

”If the Treasury were to fill old bottles with banknotes, bury them at suitable depths in disused coal mines which are then filled up to the surface with town rubbish, and leave to the private enterprise…to dig the notes up again…there need be no more unemployment and, with the help of the repercussions, the real income of the community…would probably become a good deal greater than it is.”

|

Definitely not. This was a truly global trend that peaked in the 2020 period. It also happened to be true that the inequities of the financial system were clearly visible, emerging markets continued to face financing restraints that were not felt by their developed counterparts despite seemingly similar irresponsible fiscal policies (with the exception of the GFC/Great Recession, where it was somewhat warranted). The below chart shows the actual composition of public sector debt.

Assuming that developed economies, and the elephant in the room the Federal Reserve, were to go on a hiking cycle with concerns around inflation, what is the outcome? The results are arguably not equal. Ask yourself why, despite a high inflationary print, US treasuries continue to hold their safe-haven status? Public sector debt is not the same as private after all, not when that debt is issued in your own currency. It’s the reason Chinese corporates feel significant pain every time the Fed raises rates or EMs face even greater pain overall.

We come to our first point. The answer to whether increases to the Fed Funds Rate or raises by the ECB reduce overall debt is not in fact clear. Unless nations move toward austerity, which doesn’t conversely impact their GDP in a way to significantly reduce tax receipts, all we may see is a ballooning of deficits. This is especially true of asymmetric relationships like Italy or Spain in the Eurozone or LATAM nations with US denominated issuance. They may just be faced with both inflation and ballooning deficits. A double whammy.

Following on from this, we can see a caveat. Debt may decrease via an avenue that may be unpalatable to most central banks, default. Unlike the GFC, this is not private sector but sovereign default risk. Even for those markets that have issued debt in their own currency, there is a great degree of risk that yields may skyrocket beyond manageable levels so that ever increasing issuance is required, adding to inflation. And so it goes in a vicious cycle (the most recent and obvious example of this being Turkey).

The above is the likely story of EMs and developing economies but what about so-called developed economies like the US, Eurozone and Australia.

Here the outcomes are a little more nuanced. Take the US for example, an increase in the Fed Funds rate may increase debt servicing costs but, because of the dynamics above, it may be that the subsequent rise in the USD (remember fiat is a relative game) might lead to further deterioration of the trade balance (by making imports cheaper). Thus exacerbating unemployment and assuming a further feedback loop into the political space, faced with two year election cycles, increase public sector deficits which may then perversely create further inflation.

In Australia the situation may require an even better and more nuanced dance. The majority of the debt in this country is household, driven by the residential market. Even incremental increases to the cash rate can have disproportionate impacts upon debt servicing abilities. Even assuming lenders have adhered to the golden rule of ensuring that mortgage payments only make up 28% of the households disposable income, a 50% increase in this cost (i.e. what an increase of 3% to 4.5% in the mortgage rate) would be seriously detrimental to overall consumer health.

So, will debt decrease? Under the current trajectory and policy environment (which should theoretically decrease it), on a balance of probabilities, we are likely to see an increase. This is with the cherry on top that it may not actually tackle inflation as hoped.

Is there a way out?

Using history to try navigate in uncharted territories is always a dangerous strategy. Looking to the 50s where the US, coming out of WWII, saw its debt decrease from a staggering 110% in 1945 to around 50% by 1959; how though?

Mainstream thought suggests that it was immense fiscal discipline but lets look at the numbers. The Fed effectively pegged the short rates and continued to actively cap long-term yields at 2.5% until the spring of 1951. What was the CPI over the same period? An average of 6.5% p.a.. Wage controls were dismantled and, when they kept up with rises in inflation, government receipts increased. At a deeply negative real yield for close to 15 years, it doesn’t take long before it was decreased.

But what about the global sphere?

History buffs may be familiar with the Bretton Woods Agreement that effectively ensured a certain degree of coordination between most of the so-called free markets through the maintenance of the peg to gold. This ensured that, despite the immense amount of capital required in the reconstruction effort both in Japan and Europe, that nations saw similar declines. There was no default. There was no Great Depression. What was required was great degree of coordination.

For the investor, what’s the point of knowing all that?

If we can assume that Covid measures have significantly increased risks to the global financial system in the form of sovereign default risk, debt has ballooned out and the only way is through financial repression (even if it’s not in the immediate term). Then we can safely assume which asset class provides the biggest risk: bonds (including sovereigns & Cash). At the same time, we can also look at those which provide the best possibilities for preservation of capital. We’re looking for any asset with two attributes; 1) that can take advantage of financial repression to ascertain capital cheaply (at least in real terms) and 2) have bargaining power where increases to cost of production can be passed on to consumers. On the second point we include property in the agricultural or commercial space which can generate cash-flow at pace with CPI, allocations to equities like healthcare, infrastructure, defense and consumer staples. The only exception to this, in our view, are businesses or sectors that are likely to benefit from increased government intervention Here we are looking at those linked to the green transition or transportation infrastructure as well as associated industries, including materials supply.